Beyond the printing press: alternative means of production in the global history of print

• • •

26 JUN 2019 • ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY, LONDON

One day international conference

Beyond the printing press: alternative means of production in the global history of print

• • •

26 JUN 2019 • ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY, LONDON

One day international conference

Alongside the printing press a myriad other means of production and reproduction of textual/visual matter have been a vital part of print cultures across the world. The ‘agents of change’ in the global history of printing and publishing, across the twentieth century in particular, have been other processes, mechanisms, and devices other than the printing press.

This conference focuses on the role of such alternative or additional means of knowledge production and dissemination – tools like stencils, mimeographs, duplicators, photocopiers, the processes of strike-on and rub-down lettering, cyclostyle, xerography, to name just a few – alongside parallels, intersections, and continuations: handwriting, orality, other long-standing as well as short-lived ways of communication that have shaped expectations and outcomes. Despite their marginal location in print history such means and processes have had significant influence in wide-ranging contexts of political activism, countercultures, resistance and student movements, and in confronting and challenging censorship. But they have also been indispensable in mundane office use, have permeated public spaces and discourses, and played a key role in the day-to-day personal consumption of, and access to, information.

We invite papers that examine the global history of small-scale technologies as well as the situational or selective deployment of alternative modes of information production and circulation across the world, beyond or alongside the printing press. Topics of interest include, but are not limited to, practical and theoretical aspects, business history, design and manufacture, the publications and publics of such endeavours, as well as practice-based enquiries and archival questions related to the longevity or ephemerality of their productions. The conference is particularly interested in investigations of Asian and African contexts where such alternatives may have had other functions or entirely different implications. Papers addressing oral histories, narratives of personal engagement, case studies of contextual adaptation and use are welcome, as are those that explore connections between geographical, socioeconomic, and linguistic contexts of printing through other means.

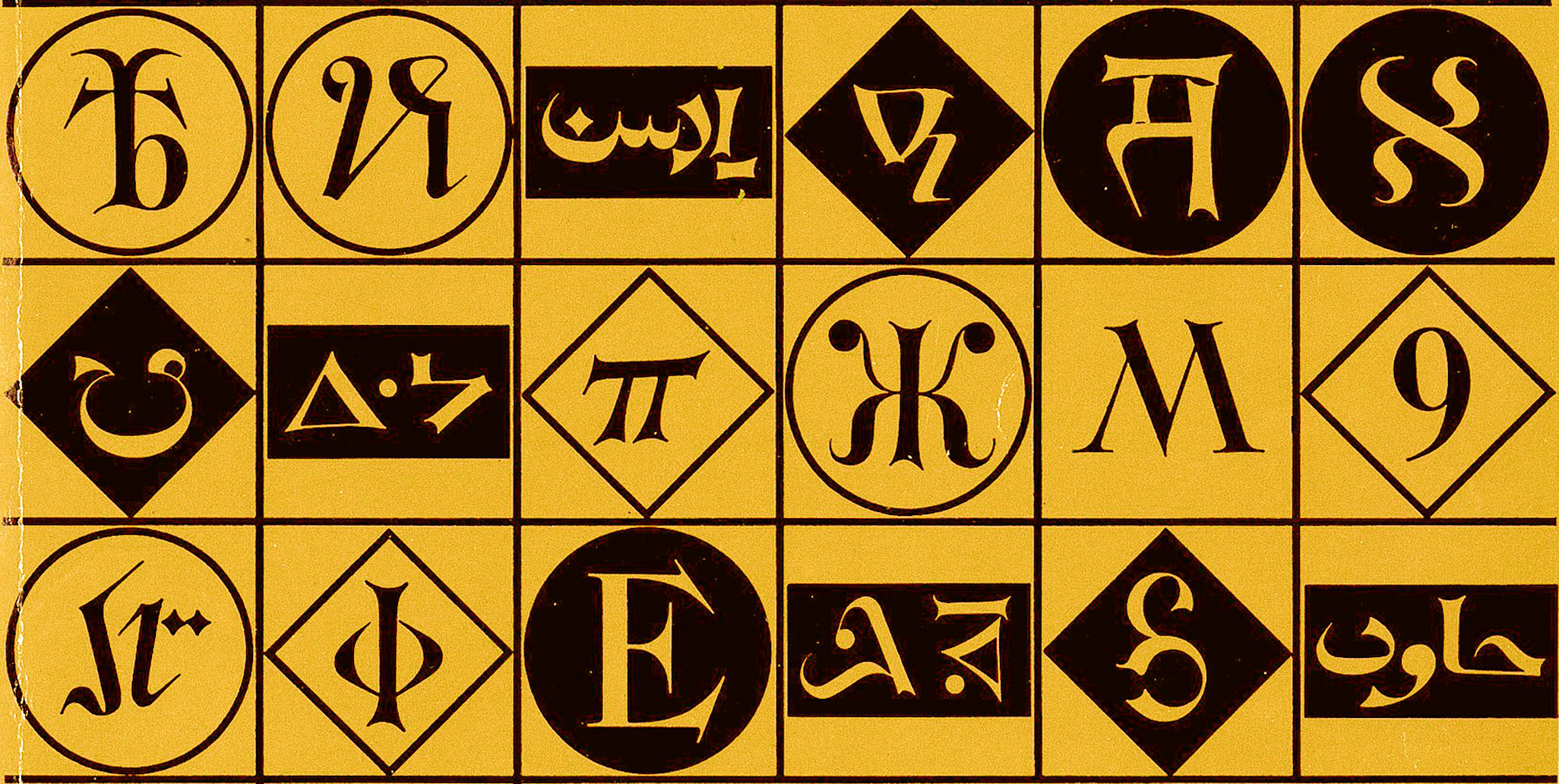

△ AN ASSORTMENT OF CHARACTERS of various writing systems of the world, on the cover of the typewriter manufacturer Olivetti’s in-house magazine Notizie Olivetti, no. 82, 1964. (Image courtesy of Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti, Ivrea)

We invite proposals for papers of 20-minute duration. Please send an abstract (300 words) and short bio (150 words) to conference@contextual-alternate.com

Deadline for abstract submission: 10 April 2019

Notification of acceptance: 15 April 2019

Date of conference: 26 June 2019

Conference venue: Lecture Hall, Royal Asiatic Society

Venue address: 14 Stephenson Way, London NW1 2HD

Conference convener: Dr Vaibhav Singh, University of Reading

Email enquiries: conference@contextual-alternate.com

We are unable to cover costs involved in travel and accommodation, however, early career researchers presenting at the conference will be reimbursed for economy travel (within UK). Tea/coffee and refreshments will be provided during the conference. Please register before 22 June 2019 as places are limited.

We would like to thank The Bibliographical Society for their generous support in making this event possible.

CF02-01

CF02-01

ANINDITA GHOSH (University of Manchester)

Print? What print? The many ways of reading, listening, singing, and (re)producing printed text in an age of print

This paper will consider the various non-standard ways in which the printed text came to be a part of the nineteenth century reading landscape in India. While print had arrived in India in the sixteenth century via the missionaries who operated in small enclaves in the southern part of the subcontinent, it was not until the nineteenth century that printing took off on a bigger commercial scale. The tremendous explosion of printed material is evidenced by the fact that between 1868 and 1905 alone about two hundred thousand titles were published - more, by far, than the total output in France during the Age of Enlightenment. Ironically, however, as I show, using Bengal as a case study, the new print technology, instead of fixing formats, genres, and languages, offered opportunities for the interplay of many forms. Most noticeably, print sustained earlier reading and writing traditions. The image of print in a colonial context – as a technology of power clamping its vicelike grip on the colonized imagination – stands considerably compromised in the light of such evidence, prompting us to reconsider the tremendous vigour and energy of this print culture. Shared imagination, collective aspirations, and multiple reading practices mingled in complex ways to encourage differentiated uses and multiple appropriations of the same material objects (books, newspapers, etc) and ideas. Under the circumstances, the message of the printed text could only have been less than totally acculturating. Songs, performances, and images based on printed works disrupted any predictable patterns of consumption that standard histories of individual, silent reading would have us believe. The strong tradition of orality, the colonial context of printing and publishing, the very dramatic and sudden coming of age of print – all contribute to making the history of the printing press in India a unique chapter in the larger global narrative of print.

△ Scene from the Elokeshi Mohanta scandal where Elokeshi is beheaded by her husband Nabin (Kalighat pat, 1875). Such images did brisk trade alongside printed texts on the case at the time in Calcutta and around. (Image courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

Anindita Ghosh is Professor of Modern Indian History at the University of Manchester. She obtained her doctoral degree from Cambridge, and joined the History Department at the University of Manchester in 2001 as a lecturer, having served as a Simon Fellow between 1999 and 2000. Her work broadly addresses questions of power, culture, and resistance. Her first monograph Power in print: popular publishing and the politics of language and culture in a colonial society, 1778–1905 (Oxford University Press) was published in 2006. She has published widely on the social history of popular vernacular print-cultures, literary taste, and standardisation in South Asia. She is a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, and serves on the editorial board of Book History. Her two part BBC Radio 4 series ‘Printing a Nation’ – a brief history of printing in India – was broadcast twice, in April and September 2017.

YAIR WALLACH (SOAS, University of London)

Metal, ceramic, stone: a textual landscape in crisis in Ottoman and British-ruled Jerusalem

The Arabic and Hebrew textual landscape of Jerusalem between 1850 and 1948 involved various artefacts which were predominantly produced as unique objects, typically by hand by artists and artisans. There were paper notices and printed advertisements, printed in the many print-shops in the city. But most texts were produced as singular artefacts: stone inscriptions in marble, in the porticos of Islamic schools or Jewish synagogues; ancient cloth banners, embroidered in golden thread; ceramic tiles for street name plates, singularly painted by Armenian artists; signs for buildings, painted by sign makers or cast in metal. In this paper I will consider the changing nature and employment of these singular artefacts, their role in shaping urban space, and the increasing role of mass reproduction in the manner in which they were produced, circulated, and read. Reproduction through photography and film captured these inscriptions and graffiti, and communicated them to foreign and local audiences. The transition to simple, bold, visible ‘logos’ of state, a visual language that expressed claims of state and nationhood, used visual motifs to make these claims. Thus the Ottoman sultan’s painted monogram circulating on signboards, metal, and stone created a space of civic Ottomanism of a new kind; and blue ceramic tiles for street name plates were chosen by British officials to reproduce the sacrality of the Dome of the Rock (and its 16th century blue ceramics) onto a larger modern city, spreading north, south, and west. My paper will explore the role of mass reproduction in the fate of these artefacts, and the manner it contributed to the rewriting of space against the backdrop of imperialism, colonialism, and nationalism.

△ Jews writing on the wailing wall, from a 1902 lithograph by Théodore Jacques Ralli. (Image courtesy of Jewish Museum, Berlin)

Yair Wallach is Senior Lecturer in Israeli Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), University of London, and the head of SOAS Centre for Jewish Studies. He is a cultural and social historian, whose research explores the intersection between ideas and material culture in the everyday experience of contested modernity in Palestine/Israel. He has written on issues of visual culture, urban space, social mobilisation, and shifting identities. His book, A city in fragments: urban text in modern Jerusalem (forthcoming with Stanford University Press) is a relational history of the transformation of Arabic and Hebrew texts in the urban space of modern Jerusalem (1850–1948).

CF02-02

CF02-02

MARK E. BALMFORTH (Columbia University)

Palm-leaf methods at the inception of print: Tamil reading practices at the American Ceylon Mission

This paper traces the social history of one of South Asia’s first publishing revolutions by analyzing how older, palm-leaf reading methods were used by students encountering the earliest printed textbooks in the region. Between 1823 and 1855, the American Ceylon Mission (ACM) press printed more than three and a half million items, spread over 290 unique publications, all totalling more than 175 million printed pages. If stacked, this tower of mostly Tamil-language Christian tracts, school books, and pancankams (sacred calendars) would stand twice as tall as Mount Everest. This stunning quantity of printed material quickly reached across the Tamil-speaking region and in the process challenged the caste-based control of text and sacred authority, but it is unclear precisely how Tamils interacted with the textual produce of mechanical reproduction. Between 1823 and 1835, when the ACM pioneered the widespread use of print in Tamil teaching, each of the mission’s Tamil instructors had been trained in a palm-leaf-saturated academic world. Recent research has demonstrated that Tamil palm-leaf didactic texts of the eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries principally served as aides-de-mémoire, or tools to facilitate the memorized, spoken word. That is to say, the palm-leaf texts used in regional, Tamil-language schools were not primarily considered repositories of knowledge, but instead were designed to cultivate verbatim retention and recitation. Descriptions of ACM classroom pedagogy make clear that the first generations of mission students who studied with print-based materials relied upon alternative, longstanding palm-leaf-centric reading practices that included group recitation, an emphasis on memorization, and standardized, oral question-and-answer examination. The use of palm-leaf reading methods in an expanding print world constitutes a meaningful moment of transition for the South Asian interaction with the written word, as texts increasingly shifted from mnemonic devices to the now dominant consideration of texts as repositories of knowledge.

△ ‘Hindu school’ from an album of Company paintings of occupations and festivals. Council of World Missions, CMWL MS 500, Folio 42. (Image courtesy of SOAS, University of London)

Mark E. Balmforth is a PhD candidate in Religion at Columbia University and manager of the Jaffna Protestant Digital Library. His dissertation is titled ‘A peninsularity of mind’: pedagogy, protestants, and power in British Colonial Ceylon, and charts the entwining of caste, nation, and gender in nineteenth-century schooling in Jaffna. Between 2016 and 2018, Mark led two Endangered Archives Programme grants to digitize and make publicly accessible archival materials related to Jaffna’s Protestant community.

Paul Bevan (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford | SOAS, London)

The cloth banknote of the Sichuan-Shaanxi Soviet Government Workers and Farmers Bank

In China, during the turbulent decade of the 1930s, a number of Chinese soviet areas (also known as revolutionary base areas) were formed as a direct reaction to the violent government crackdown that had taken place, since the late 1920s, on the membership of left-wing organisations. The most extensive of the soviet areas, where large numbers of communists made their homes, was the Jiangxi Soviet, established by Mao Zedong in 1931. In one lesser-known soviet area, the Sichuan-Shaanxi Soviet, the regional government decided to use cloth as an alternative to paper to print their banknotes. This cloth banknote was printed using one of three printing presses commandeered from local warlords, and distributed by the Sichuan-Shaanxi Soviet Government Workers and Farmers Bank in 1933. In common with a number of paper examples produced by similar communist organisations, it displays many of the common symbols associated with the worldwide socialist movement: the hammer and sickle, the clenched fist, and Marxist rallying cry ‘Workers of the world, unite’ translated into Chinese. Examples in various denominations, in shades of grey or blue, printed on heavy cotton cloth can be seen in museum collections worldwide, including, in the UK, in those of both the Ashmolean and British Museums. The reverse of the cloth banknote is particularly striking and shows a design that features a number of large stylised Chinese characters. Although done in a way that is not immediately intelligible to readers of Chinese, on close examination this can be recognised as a stylised rendering of political slogans done in imitation of Soviet Russian Constructivist design, the Chinese characters themselves ingeniously formed into the shape of a printing press or other industrial machinery. It is this Constructivist design that makes it unique amongst banknotes in China. Such approaches to typographical design were also used by publishers working for left-wing periodical presses in Shanghai and were related to a widespread form of art work associated with modern ‘Art Deco’ design in China. The magazines produced as a result of this were, in turn, connected to an adoption of design elements found in left-wing magazines worldwide, which ultimately had their origins in the USSR and arrived in China via Japan in the 1920s. It is this aspect of Soviet Russian art and design, adopted by the creators of the cloth banknote in this remote area of China in 1933, that makes it significant in the fields of numismatics, textile history, and the history of art and design in China.

△ One Ch’uan cloth banknote issued by the Sichuan-Shaanxi Soviet Government Workers and Farmers Bank, 1933. (Image from private collection)

Dr Paul Bevan is Christensen Fellow in Chinese Painting at the Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford and Research Associate at the School of Oriental and African Studies. He has taught modern Chinese literature and history at the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, and SOAS, London. His first book A modern miscellany: Shanghai cartoon artists, Shao Xunmei’s circle and the travels of Jack Chen, 1926–1938 (Leiden: Brill, 2015) was hailed as ‘a major contribution to modern Chinese studies’. His second offering, Intoxicating Shanghai: modern art and literature in pictorial magazines during Shanghai’s Jazz Age, is in the final stages of publication. His wide-ranging research interests focus primarily on the impact of Western art and literature on China during the country’s Republican Period (1911–1949).

CHARLOTTE BISZEWSKI (Eugeniusz Geppert Academy, Wroclaw)

Mechanics of change: resistance, printed ephemera, and ‘alternative futures’

Underground (‘second circulation’ or ‘samizdat’) publication has existed in Poland since the 16th century. During the 1980s it reached a semi-industrial level and was available to a large proportion of the public. Such publication included calendars, pamphlets, and postcards that were used for spreading messages of solidarity and to critique the government. Satirical, witty, and dangerous, these small and rough pieces of ephemera represent significant acts of resistance. This paper will use a printmaker’s perspective to extend a different understanding of the materiality of these print objects – as products of not just the political climate but conscious socio-economic choices made by the printers. In the light of the rich history of samizdat publications, this paper also examines what old out-of-date printing technologies represent today. The paper will build on the argument that the qualities of such modes of production may not be about nostalgia alone, but that they may also be ‘critical and productive of alternative futures’. In order to do this, my research embraces and explores means of re-enactment, workshops, and artistic production. I intend to situate archives of underground print ephemera in a contemporary landscape through my work with Art Quarter Budapest in developing a reflective body of hand-made prints using DIY approaches. By employing a reconditioned mimeograph for production, often considered a lower-form of print, my paper evaluates the significance of this tool in underground print movements. This body of work, inspired by the collection of the Open Society Archives in particular, will explore the performance and ritual of printing, providing not just an understanding of the archival collection, but also the insights from alternative modes of production that are relevant today and can be carried forward.

△ Blok znaczków podziemnych ‘Poczta kolporterów’ [Sheet of unofficial stamps ‘Distributors press’/Poczta Kolporterów (ca. 1985) HU OSA 300-55-7_1-3-1. Records of the Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty Research Institute. Polish Underground Publications Unit: Printed Ephemera. (Image courtesy of Open Society Archives at Central European University, Budapest)

Charlotte Biszewski is a PhD student at the Academy of Fine Arts Eugeniusz Geppert, in Wroclaw. Her research revolves around narrative and inter-disciplinary printmaking. She works as a community artist, printmaker, and creative print technologist. After graduating in 2015 with an MA in Multidisciplinary Printmaking from the University of the West of England, she spent two years researching the Bristol Print Industry. She has presented her research through talks, a variety of publications, and a documentary film ‘Bristol set in print’, which was a finalist at the Social Machinery Film-Festival. Other awards include the Rebecca Smith Award for fine-art printmaking, the David Cantor Memorial Award for printmaking, and the Visegrad Scholarship from the Open-Society Archives.

JAMES A. FLATH (Western University, Canada)

The New Year woodblock print as an alternative to lithography in modern China

This paper examines the Chinese technology of polychrome woodblock printing commonly known as nianhua or ‘New Year woodblock print’. Nianhua were widespread throughout late-imperial China and were used to disseminate a variety of graphic themes, ranging from theatre and narrative illustrations to religious icons and what might be called ‘proto-news’. The introduction of lithography in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth century presented a serious challenge to nianhua printers both in terms of relative efficiency of the technology and the aesthetic quality of the lithographed image. Woodblock printing nonetheless endured as a commercially viable alternative to mechanized lithography for several decades. This paper will focus on the period between 1890s–1920s, when woodblock printers retained traditional styles and techniques while adjusting content to capture a share of the market for modern graphic imagery. I argue that by retaining an alternative to mechanized lithography, nianhua printers also presented their clientele with an alternate vision of modernity. This hypothesis will be examined through the analysis of nianhua depictions of modern technology, geopolitical events, fashion, and urban environments.

△ ‘A hundred seeds spill from an open pomegranate’, New Year woodblock print. Heping Printers, Yangliuqing, China. Ink on paper, c.1925, 109 x 59 cm. (Image from private collection of James A. Flath)

James A. Flath graduated with a PhD in History (Modern China) from the University of British Columbia in 2000. He is Professor of History at Western University in Canada. His first monograph, The cult of happiness: nianhua, art, and history in rural North China (UBC Press, 2004) examined the world of the North China village through the medium of folk print (nianhua), and he has expanded on that theme through subsequent articles on related topics examining the theme of ‘alternate modernity’. His second area of research is in museums, monuments, and heritage conservation sites. His monograph, Traces of the sage: monument, materiality, and the first temple of Confucius (University of Hawaii Press, 2016) studies China’s principal monument to Confucius – Kong Temple in the sage’s hometown of Qufu. His current research focuses on the effect of natural and manmade disaster on Chinese architectural heritage.

CAMILLO FORMIGATTI (Bodleian Library, Oxford)

Sanskrit manuscripts, lithographs, and incunabula: notes on print terminology and layout

Although printing presses were already known in South India in the second half of the 16th century, apparently it is in Kolkata in 1792 that the first Sanskrit text was printed with movable types. The diffusion of movable-type print in nineteenth century India is paralleled by the widespread use of lithography as a means of text reproduction. This paper will investigate the terminology for print as exemplified in selected Sanskrit incunabula from the first two decades and lithographs printed in the second half of the nineteenth century, comparing it with the terminology found in colophons of Sanskrit manuscripts from different periods and areas. The format and layout solutions of early Sanskrit prints will also be shortly discussed.

△ Manuscript (IND) 4.5.3 Padma. 5, fil. 1r. (Image courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, Oxford)

Camillo Formigatti studied Indology and Sanskrit as a secondary when he was studying Classics at the ‘Università Statale’ in Milan. After that he spent ten years in Germany, learning Tibetan and textual criticism in Marburg and manuscript studies in Hamburg. From 2008 to 2011, he worked as a research associate on the project ‘In the margins of the text: annotated manuscripts from northern India and Nepal’, in the research group Manuskriptkulturen in Asien und Afrika, funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. He worked in the Sanskrit Manuscripts Project at the University of Cambridge from 2011 to 2014. Currently he is the John Clay Sanskrit Librarian at the Bodleian Library in Oxford.

VAIBHAV SINGH (University of Reading)

The elusive writing machine: typewriters in India and the new age of manuscript production

Almost simultaneously with their commercialisation in the late nineteenth century, typewriters posited an apparatus as well as a practice that could be extended – at least in theory – to any language, any writing system of the world. Soon, typewriting manuals for languages as diverse as Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, Thai, Hindi, etc began to outline a universalist framework. This was a framework to go beyond the particularity of scribal practices in different parts of the world, towards a global method of ‘text input’, and a global document genre of the typewritten manuscript. Coinciding with the rise of the modern office and the multinational corporation as both spaces and forces of globalisation, typewriting occupied a crucial role in inscribing and reifying transnational imaginaries of communication. Not only the apparatus could be imagined to be the same across languages and scripts, the posture, the furniture, the office space, workplace hierarchies, and gender relations too would be extended across cultural boundaries. A typewritten document in any language could be characterised as an artefact defined by a ‘modern’ machine, rather than by writing tools loaded with cultural/aesthetic traditions. Unlike previous paradigms of manuscript production that were dependent on and represented skilled practice in a culturally particular sense, typewriting presented a discourse of globalised communication and modernisation. Firstly, through its mechanism: any ‘modern language’ (but really the script), it claimed, would have to be adaptable on the keyboard – if not, the language and writing system itself needed to be ‘modernised’. Secondly, the discourse of global practise extended to the layout and organisation of information, the composition of the typewritten document itself, redefining the ‘manuscript’ across regional and national boundaries. This paper aims to offer a glimpse into the broad spectrum of material and ideological negotiations behind the long engagement with typewriters in India – focusing on the resourcefulness not only of designers, entrepreneurs, and manufacturers, but also that of adapters and users of writing machines outside printing offices.

△ A draughtsperson, identified only as Mr. Giacosa of the Technical Office at Olivetti, designing a Devanagari character for the company’s Hindi typewriter, 1956 (Image courtesy of Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti, Ivrea)

Vaibhav Singh is currently a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Reading. He trained as a typographer and typeface designer and was the recipient of the Felix scholarship for his doctoral research, which examined the twentieth-century history of typographic design and technological developments in India. His research interests revolve broadly around the history of printing, publishing, design, and technology, with an emphasis on multilingual South Asian contexts. Recent projects have focussed on labour and working practices in the printing industry, transformations across technological change, and transnational professional and commercial networks of print.

DEBORAH SOLOMON (Otterbein University, Westerville, Ohio)

Gariban print technology in colonial Korea

A number of new print technologies were introduced to the Korean peninsula with formal Japanese colonization in 1910. One such technology was the gariban or toshaban, a simple, portable mimeograph-style device first patented in Japan in 1894. While scholars have considered the social and cultural implications of gariban use within the Japanese islands, its vast and wide-reaching impact in Japanese colonial contexts has been overlooked. In this paper, I assess the importance of gariban printing on the Korean peninsula through analyzing company marketing materials and both Japanese and Korean documents produced using gariban devices. The company that produced the gariban expanded production and opened its first branch office in Seoul in 1912, selling gariban devices to the Government-General of Korea as well as to the general public. Company marketing in Korea specifically targeted Japanese residents, and encouraged them to use gariban to produce publications that resonated with local and regional Japanese settler communities. Official use in Korea diminished over time (although never entirely disappeared) with the introduction of newer, more effective methods of printing. In contrast, however – in part due to sustained targeted marketing campaigns – demand for gariban devices within Japanese settler communities increased throughout colonial rule. In addition, during this same time period, members of anti-Japanese, pro-independence Korean resistance movements also began to rely more and more on gariban printing as an efficient means of creating and disseminating protest manifestos and other illicit writings that could be easily moved and kept hidden from colonial authorities. By analyzing the range of materials produced by and about gariban printing in colonial Korea, I argue that this print technology played a key role in not only reinforcing and expanding dominant Japanese colonialist discourses on the Korean peninsula, but also in diversifying resistance narratives that formed in opposition to them.

△ Mimeograph duplicator (left) and the stylus (right) used for creating a master for the copying process. From Shoko Shimura, Gariban bunka o aruku: toshaban no hyakunen, Tokyo: Shinjuku Shobo, 1995, p. 224. (Image courtesy of Contextual Alternate)

Deborah Solomon is Associate Professor of East Asian History at Otterbein University in Westerville, Ohio. She received her PhD in modern Korean and Japanese history from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and completed a joint post-doctoral fellowship at the Korea Institute and the Reischauer Institute for Japanese Studies at Harvard University before joining the Otterbein faculty in 2010. She is a member of the Ohio State University’s Korea Institute Advisory Committee and was a Center for Japanese Studies Visiting Scholar at UC Berkeley in 2018. From 2013–2015, she served as a Junior Fellow in the Mansfield Foundation US-Korea Scholar-Policymaker Nexus. As a historian of modern Korea, her scholarship centres on the Korean peninsula under Japanese rule prior to 1945. Her current book project, Schooling discontent: education, identity and student protest in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945, examines resistance to Japanese rule within the context of evolving Korean student identity.

MEI XIN WANG (British Museum, London)

Tracing the origins of Chinese printing: four thousand years of seals and sealing practice

Printing, together with papermaking, gunpowder, and the compass, is known as one of the four seminal inventions made by the ancient Chinese. Calligraphy, copied and engraved on stone, was the earliest form of reproduction that dated back to the Han period (206BC–220AD). But it was in the 8th century during the Tang dynasty (618–907AD) that the production of printed materials using carved woodblocks was invented and gained popularity. The need to produce large amounts of printed literature due to political, social, and religious changes, together with the wide use of paper in China, gave impetus to this invention. However, Chinese seals and sealing practice played a key role, both before and after, in the history of printing. Chinese seals have a history of over four thousand years. Similar to practices in other civilizations, Chinese seals were stamped in clay before paper became widely used. Although Chinese seals were used for the purposes of authentication, identification, and authorization in the early period, the technique and practice of inscribing and engraving written characters on the seals to make impressions was in fact instrumental in the advent of print. In this paper, I will attempt to trace the history of Chinese seals and sealing practice to illustrate how the development of Chinese seals contributed to the invention of woodblock printing and revolutionalized the way information is disseminated.

△ Left: printing block made of pear wood, Qing dynasty (1644–1911) BM 1909, 0519.2. Right: rubbing on paper, Northern Wei dynasty (386–534) BM 1975, 1027 0.6 (Images courtesy of the British Museum, London)

Mei Xin Wang is China Resource Specialist in the Department of Asia at the British Museum. Her research interests include Chinese seals, Chinese lacquer, and early twentieth century Chinese ceramics. Her paper ‘Chinese seals: stamps of status on Chinese paintings and calligraphies’ was published in the British Museum Research Publication, 2018.

RIGZIN CHODON (Ladakh Arts and Media Organization, Leh)

Early twentieth century missionary newspapers in Ladakh and Kyelang

The monthly newspaper La dvags kyi ag bar, in the Tibetan script, published by Moravian Missionary August Hermann Francke between 1904–10, was the first of its kind in the Ladakh region. It was printed on a lithographic press from Khalatse village in Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir, with the idea of imparting Christian teachings using the local language and script. The paper was revived in 1927 by Rev. Walter Asboe from Kyelang in Himachal Pradesh and subsequently in Leh with the titles Kye lang ag bar and La dvags pho nya respectively. The papers were printed using a flex duplicator to serve the same purpose as the lithographed original. The first monthly paper followed the idea of using the local script, to which notions of sacredness were closely associated as Buddhist religious texts was written in the same script. News – local, national, international – constituted an important section of the paper, which also contained local maxims and local folklore adapted to offer Christian moral lessons to readers. The contents of the paper thus formed an interesting blend of local oral traditions and scriptural practices with biblical and secular knowledge. The revival of the paper introduced a different approach. It included practical advice and imparted new knowledge relevant to day-to-day practice – like the use of chimneys and kitchen hearths, growing new kinds of vegetables, improved farming techniques etc. Visual representation in the form of hand-drawn illustrations in the paper from 1927 onward also presented a different approach to communication and knowledge exchange. These monthly newspapers published at the Kyelang Mission House in Lahaul and Leh Mission House are full of new ideas – they can be seen as an avant-garde forms of writing, as collaborative textual and visual productions, providing space for many local writers to publish their works and establish new modes of expression. By highlighting these novel forms of writing as well as different means of production employed by these newspapers, I aim to examine how lithography and duplicating machines served as alternative means of knowledge exchange during a period when woodcut prints of Buddhist liturgy were the common and dominant paradigm of printing in the region.

Rigzin Chodon is based in Leh, Ladakh, Jammu & Kashmir. She is currently a Research Associate at the Ladakh Arts and Media Organization, Leh. She completed her PhD in 2018 from the Centre for English Studies, School of Language, Literature & Culture Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Her thesis is titled ‘Language, politics, and identity: a study of missionary newspapers in Ladakh and Kyelang (1908-10, 1927-35, 1936-44, and 1952-59)’.

ZAHRA SHAH (Government College University, Lahore)

The persistence of typography in a world of lithography: print industries in nineteenth-century north India

In colonial north India, lithographic presses provided the means to print works in the Perso-Arabic script that were cheaper, easier to produce and more popular than their typographic equivalents. Despite these shortcomings, typographic techniques continued to be employed alongside lithography for much of the nineteenth century. This paper asks why certain actors chose to employ typography in an industry dominated by lithography. While it is commonly understood that lithography offered the opportunity to produce texts that were more aesthetically appealing to Persianate readers, the persistence of typography has not yet been critically examined or explained. Indeed, it is usually assumed that the introduction of typography provided the circumstances for lithography to emerge and find markets in the first place, and that different printing techniques were informed by comparable motives. By situating both techniques in the broader terrain of printing in the Indian subcontinent, this paper will challenge such views and examine the ideological underpinnings that governed the production, distribution, and consumption of texts in each form. Works produced by different means appear to have appealed to disparate groups of readers, and encouraged different kinds of textual engagement. Scrutinizing the types of texts produced by typographic and lithographic means, respectively, this paper will investigate the extent to which each industry projected different images of the subcontinent’s literary heritage, contributing to the shaping of distinctive socio-textual communities from Calcutta to Lahore. In so doing, this paper stresses the need to examine diverse forms of textual production simultaneously in order to understand the ways in which books with identical contents could generate radically different meanings.

Zahra Shah received her DPhil in History from the University of Oxford in 2017. Her doctoral thesis, entitled ‘Between classical and cosmopolitan: Persian in early colonial India, c.1757–1857’, examined Persianate literary culture in north India and sought to understand the changing social relations underpinning literary production and circulation under the British East India Company. Her current research interests include early modern and colonial Indian literary cultures, the history of the printed book in South Asia, and female authorship in eighteenth-century India. In March 2018, she joined the Department of History at Government College University Lahore as Assistant Professor.